Russian Americana: Pussy Riot and the Violence of Consent

The artivist (art + activist) punk collective Pussy Riot entered the world stage in February of 2012 after they entered Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, donned their iconically eccentric and brightly colored balaclavas, tights, and dresses, and staged their “Punk Prayer” action, which resulted in three of the members being charged with hooliganism and sentenced to two years of hard time in penal colonies. This of course was not their first foray into social protest; the collective had participated in a number of actions prior to this. Originating in 2011, with some members having been active previously in other anarchist art collectives such as Voina (Russian for “War”), they sought to fight for the human and civil rights which had been suppressed by the Russian ex-KGB autocrat Vladimir Putin.

Although not strictly a musical act, Pussy Riot have recently made the music festival rounds in the U.S. so as to spread their political hijinks to a wider American audience. Since 2016, with the campaign of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, Pussy Riot began collaborating with English speaking artists and producers to release their album XXX, which contained the songs “Make America Great Again,” “Straight Outta Vagina,” and “Organs.” They extended their artistic touch by releasing accompanying music videos that worked to visually accentuate the provocative lyrics with feminist iconography and anti-authoritarian/post-Orwellian attacks on state power. Since then they have also released the songs “Police State” (2017), “Bad Apples” (2018), “Bad Girls” (2018), and “Track About Good Cop” (2018) to American audiences.

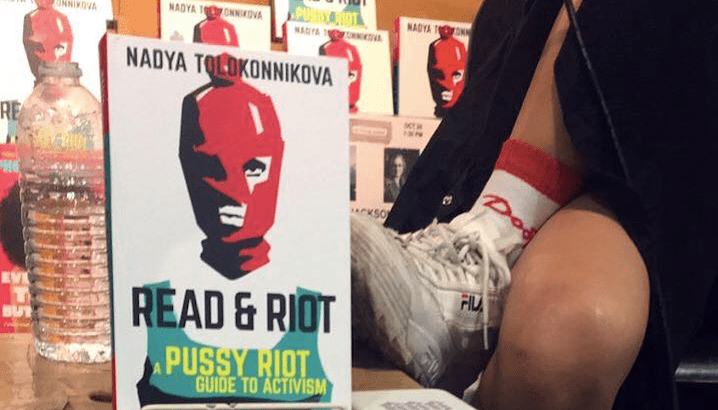

There are many, of course, who object to any person(s) who attempt to take a political stance towards the U.S. when they are not themselves citizens. For this reason, it is worth pointing out that Nadya Tolokonnikova, in her recent guide to activism “Read and Riot,” states as their earliest of role models the philosopher Diogenes the Cynic. Diogenes is renowned as Socrates’ nemesis, who would defecate and masturbate in public, walk around Athens with a lantern in broad daylight looking for an “honest man,” and is the first known person to explicitly consider himself as “a person of the world” rather than state or institution (Socrates was so committed to his identity as an “Athenian” that he willfully drank the hemlock he was condemned to drink out of duty to the consequences of having broken the laws which he was obliged to obey). Although the group’s antics began as protest against the conservative regime ruling Russia, they have since expanded their critique to the U.S. with the rise of nationalism and Trumpism in an attempt to highlight the similarities of our plights.

There is little need to delve into the controversy concerning the relation between Putin and Trump, but what is important to highlight is that both are committed to the notion of exceptionalism and represent business ethos taking over democratic institutions – both features of neoconservative and oppressive societies. It is worthwhile also mentioning that in Putin’s Russia, whenever citizens complain about civil rights, Putin has been known to refer to the suppression of civil rights in the U.S. with the examples of Guantanamo Bay and the extrajudicial killings by police. The motivation behind Pussy Riot is thus to bridge the barriers that often separate us both politically and geographically in order to enjoin us as a world community in the fight for liberty for all. During this time of rising nationalism, it is an important feature to point out, for it is only together that we can unite to bring about the changes we like to speak about with such lofty rhetoric but hardly ever enact despite something as artificially and arbitrarily contrived as borders.

I am a firm believer in the idea that no art is apolitical. Whether or not you are explicitly objecting to or supporting social groups and causes, one’s art is always a reflection of one’s power as well as socio-economic status. Pussy Riot, who take their heritage from the Riot Grrrl phenomenon of the ’90s with bands such as Bikini Kill and 7 Year Bitch, resurrect a tradition of de-stultifying politics by making it something that is artistically and personally more impactful and relevant once again. It is a fight against apathy and the tendency to lose hope in our own abilities to affect change. One of the premises of such activities is that the state of the world is the consequence of our actions. If we don’t like how things are, it is therefore in our power to change it. And a large part of changing the world is by raising consciousness. Acts like Pussy Riot work therefore to recuperate mass media with a subversive message in order to use the system against itself. As they say in leftist circles: Educate. Agitate. Organize.

The indelible spirit of these artists of change is best described in Nadya Tolokonnikova’s words: “The future has never seemed so full of and rich in wonderful possibilities as when I was in a labor camp and had literally nothing but dreams.” Nadya spent a good portion of her sentence in a Mordovian prison camp, considered to be one of the harshest in all of Russia, and for a time disappeared within the system during which many feared for her life. Yet both Nadya and Maria Alyokhina (Yekaterina Samutsevich, the third accused, had her prison term suspended) were able to speak up against the deplorable prison conditions and have been able to bring some reform which they continue to advocate. What I find so remarkable in these individuals is that, although I’m sure they experienced moments of extreme doubt, they turned their situation around by making it a fortifying experience which they then used to hit back even harder and this time with a wider audience.

The point is that so long as we just accept things as they are or simply ask politely that others maintain society’s standards, nothing will come of it. We must be vigilant and, if necessary, militant to bring real positive change. In regards to how Tolokonnikova was able to bring about some good during her time in the labor camps, she states in “Read and Riot,” “That’s how I learned that nice talks never work with those who have power over you. That’s how I learned that sometimes there is no other option than showing your teeth and going on the warpath.” Today we are told to be civil while protestors are run down in the streets with legislation designed to appease the aggressor and where toddlers are expected to represent themselves in court. But when those in power hold the house edge they will always have the upper hand, and so when we play on so-called “equal” footing we are already at a disadvantage.

Pussy Riot isn’t about making music. Music just so happens to be one of the best vehicles to deliver their message and disrupt conventional spaces. They do not restrict their actions to fairgrounds nor stadiums. The streets are their stage. I doubt whether they even care if you like what they say or how they say it. The situation is probably all the better if you don’t, for if that is the case it means you have received their message despite that and now must make a decision: consent to how the world is by disregarding them or share their message and even hopefully take up action because of it. Neutrality is a myth. Inaction is consent, and in times of trouble such consent can result in real violence. What form your action takes is up to you, but it is imperative that we do something. As another inspiration to the collective, Václav Havel, notes in his essay “The Power of the Powerless:”

The terms “dissident” frequently implies a special profession, as if, along with the more normal vocations, there were another special one – grumbling about the state of things. In fact, a “dissident” is simply a physicist, a sociologist, a worker, a poet, individuals who are doing what they feel they must and, consequently, who find themselves in open conflict with the regime. This conflict has not come about through any conscious intention on their part, but simply through the inner logic of their thinking, behavior, or work… They have not, in other words, consciously decided to be professional malcontents, rather as one decides to be a tailor or a blacksmith. “Dissent” springs from motivations far different from the desire for titles or fame. In short, they do not decide to become “dissidents,”…[it is] primarily an existential attitude.”

As such, there is no quantitative measure of “dissent,” and courage reveals itself in different ways and in different degrees by different people. The point is that we act in some manner no matter how small. The world is in our hands, and it is up to us how it looks.